Green media briefing – a brief history of media and the environment

With disaster scenes growing across the world, environmental issues have made it to the top of the news agenda as, perhaps, never before.

2021 finally saw (most) world leaders make it to Glasgow for the postponed COP26 to thrash out what we need to do next for the planet. It has been billed as critical, but has also been said to have fallen short of what is required.

Yet some will remember headlines made during the Rio ‘Earth Summit’ in 1992 – which paved the way for the 2015 Paris Agreement, the first binding environmental treaty of its kind – maybe, even, the first such global environmental convention, in 1972.

This is all, in some ways, old news. So why are we consistently failing to take the action needed?

We may point to governments, corporations and even ourselves – but what role does the news media, as public informer, and as an industry with emissions and other environmental harms of its own – have in this?

This ‘green media briefing’ – based on PhD research being done at the University of Central Lancashire supported by WAN-IFRA – will share the latest on the ‘footprint’ of the news media, and its so-called ‘brainprint’, or its power to influence people, and the connection between the two.

Ahead of a discussion about what’s next for ‘green media’ at the Virtual World News Media Congress 2021 on 2 December at 14h CET, where we’ll hear from industry leaders at the University of Oxford, the French publishers’ Alliance Presse and the Nordic news media giant Schibsted, we wanted to take a look back.

A brief (and no doubt incomplete) history of media and the environment

1300s

Mass printing begins, initially using unwanted rags, then by felling trees, and using water as an ingredient and to fuel production (Maxwell and Miller, 2012).

1400s

Gutenberg brings the mechanical printing press to Europe – the use of which requires mining for copper, lead, tin and antimony, and used polluting materials such as lampblack and dangerous chemicals like turpentine (Maxwell and Miller, 2012).

1600s

British politician and philosopher of science Francis Bacon writes “printing, gunpowder, and the compass…. these three have changed the appearance and state of the whole world” (1620). This is perhaps the first connection ever made between media innovation and the global environment.

Because of the environmental damage done from this point, a paper from geologists writing in Nature pinpoints 1610 as the potential start of a new geological time period – the so-called Anthropocene, or the age of humans. They suggest “colonialism, global trade and coal” have brought this about (Lewis and Maslin, 2015).

1800s

The rise of coal and steam power brings mass paper production, huge demand for wood and the dawn of advertising, alongside the development of the first batteries (Maxwell and Miller, 2012). Batteries are made of different non-renewable natural materials, and can contribute to water and air pollution, and negatively affect our health, if not disposed of properly.

Writing in 1800 and 1831, German explorer, philosopher and scientist Alexander von Humboldt is credited with being the first person to identify what we now understand to be man-made global warming (Wulf, 2015). Later, in 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius is the first known person to demonstrate through experiment the relationship between carbon emissions and global warming (in McKibben, 2012).

1900s

The age of electricity brings telegraphy, industrial printing, telephones, radio and TV, using ever-more coal and copper, and bleach and solvents, resulting in significant water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Maxwell and Miller, 2012).

In 1972, Limits to Growth (Meadows et al., 2009) was first published, commissioned from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by the Club of Rome alongside the World3 computer simulation model. It showed that the environmental impacts of humans could not increase beyond the “carrying capacity of the Earth” (p. xv) – if the number of Earths remained constant – at one. That same year the first-ever global environmental summit was convened – the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment – out of which came the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Most-oft-cited as a basis for work on achieving sustainability is the UN’s 1987 Our Common Future report, which established “sustainable development” as a goal where “development meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987). It was created by the Brundtland Commission, which was established to recapture the spirit of the 1972 conference and paved the way for a number of actions agreed at the next environmental summit.

The 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, or the Rio ‘Earth Summit’, was held on the 20th anniversary of the 1972 event. It is where the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established, along with a number of principles related to sustainable development.

2000s

The age of mass consumption brings personal computers, laptops, monitors, keyboards, games consoles, mobile phones, tablets, smart home devices, cell towers, wifi infrastructure, satellites, social media, streaming – all of which require raw materials, often mined using lots of clean water, manufacturing and assembly, transportation and energy for use – all with a product lifespan and waste disposal issues.

The 2015 ‘Paris Agreement’ becomes the first legally binding environmental treaty of its kind – committing signatories to “limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels”. It is, yet, criticised for only requiring countries to make their own nationally determined contributions, which have in total fallen short of what is required to meet the goal.

A whole range of organisational and industrial initiatives are now trying to deal with these issues – as well as responding to new global directives coming out of the latest climate talks – which we’ll explore more in a later briefing.

References

Brundtland, G. (1987). Our Common Future. World Commission on Environment and

Development. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

Lewis, S. and Maslin, M. (2015). ‘Defining the Anthropocene’. Nature, 519(171–180). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258

Maxwell, R. and Miller, T. (2012). Greening the Media. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meadows, D. H., Randers, J. and Meadows, D. L. (2009). Limits to growth : the 30-year update. [3rd. ed.]. London: Earthscan.

Wulf, A. (2015). The invention of nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s new world. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

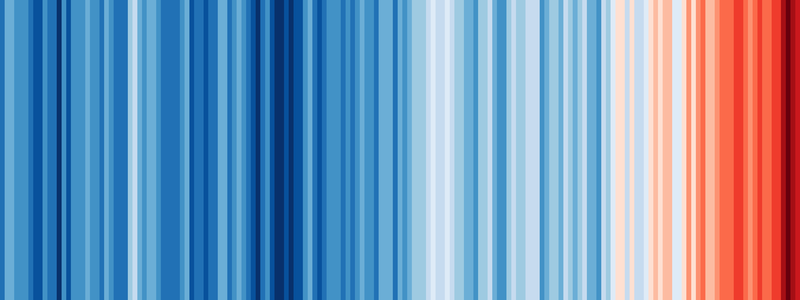

Image credit: Ed Hawkins (2018) Warming stripes for 1850-2018 using the WMO annual global temperature dataset – licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.