Schibsted: after two centuries of innovation – people and planet are now the lead story

As a finance person by background, Britt Nilsen may not be considered your average ecowarrior, or indeed, your typical innovator.

But it is precisely her understanding of the numbers that has helped Norwegian media giant Schibsted put environmental sustainability at the centre of the organisation.

“You don’t have a separate strategy for sustainability, it needs to be anchored in,” she explains, although no doubt similar organisations haven’t got that far yet.

Schibsted has almost 200 years of work under its belt – and after becoming a public limited company in the 1980s, then getting listed on the stock exchange in 1992 – its reputation has grown outside of its native country.

A decade into buying new media companies and creating its own, even while the Dotcom Bubble expanded and subsequently burst, in 2007, Harvard Business School professor Bharat Anand told the New York Times this company was “something quite special”.

In 2001, for example, after 160 years delivering newspapers, Schibsted launched its Distribution Innovation company. It has, most recently, been using AI and machine-learning to learn even more about getting news to your door – not least, how to do it better while protecting the planet.

Schibsted’s core news media business now extensively covers both Norway and Sweden – nine news brands along with their associated multimedia offerings – styled as Schibsted Norway and Schibsted Sweden respectively.

And the company has been successful, compared to many international counterparts, at converting people into online subscribers.

“It looked really dark at one point,” Nilsen admits, “but that has been a huge success. We have a lot of online subscribers and it’s increasing.” She puts some of this down to a relatively strong level of trust in news media in the Nordic countries.

“Of course, we’re still reliant on the advertising part. But we are trying to turn around the business so that the online newspaper will be a standalone, financially safe business. So that is important.”

Investments and marketplaces

Along with its Next portfolio of investments in everything from consumer finance to dating apps, Schibsted has found greater success with marketplaces than something like the UK’s Guardian did in its former ownership of used car exchange Autotrader.

Its latest big deal has seen marketplace group Adevinta spin out of Schibsted, while buying up eBay’s Classifieds business, which includes websites like Gumtree, for around $9 billion.

Its latest big deal has seen marketplace group Adevinta spin out of Schibsted, while buying up eBay’s Classifieds business, which includes websites like Gumtree, for around $9 billion.

When the transaction is finalised early next year, Nilsen says Adevinta will be the “world’s largest marketplace”. But this isn’t simply a story of diversification.

“We are trying to have people move into circular consumption instead of being in the linear element. Other things we are thinking about are, is it possible to kind of make a ‘circularity index’, or a kind of a stamp on new products or used products? Then if you have to buy new things, you should at least buy quality and know ‘this is the value that you can sell it for after three or four years’, for example.

“On 12 of our marketplaces in 2019, we have calculated the effect on the environment and also on how many materials we are saving by trading second hand, instead of having to produce a new one and throwing away a used one.”

“If you want to buy, for example, a sofa and then a message comes up ‘OK, if you buy this sofa, you will save this much CO2 emission and this equals the production of three sweaters’, for example. And then, on their account, they will accumulate the effect and how much they have saved.”

And yet still, Nilsen explains, until three years ago, sustainability was “something on the side”. “It was more like a compliance issue, following laws or regulations and commitments. We are a participant in the U.N. Global Compact and all that stuff.”

That was until the autumn of 2017, when two diversity challenges struck at once.

“We had a reorganisation in Schibsted, where at that point we had put into two business areas, media and marketplaces. And when they set their management teams in those two business areas, and also on the group level, it had a really low female ratio.

“And it was a really huge uproar, both internally and externally. ‘How is it possible in 2017 to do such a stupid thing? This is Norway!’.

“And, at the same time, #MeToo hit. And on this side, of course, we set the agenda with our newspapers.”

Incentivising diversity

In December 2017, Schibsted set goals for gender equality – a ratio of 40:60 either way on the three highest management levels by the end of 2020 – that had consequences.

“For 2018, they set short-term goals and that was like ‘we should have a new recruitment policy’, ‘we should have a diversity and inclusion policy’, ‘we should have unconscious bias training for managers and recruiters’, ‘we should establish some networks for women’.

“And also in the busiest business areas, this was more detailed like, ‘this is how many men and women should be on the long list, the short list and how many should be hired’ and so on. Really detailed.

“But the smart thing was that they put it as part of the top management’s incentives.”

The result was that, in one year, across all the management groups in their companies, the percentage of women leaders went from 34 to 39 per cent.

Until this point, environmental sustainability issues had been owned by the group’s communications team, meaning it was considered part of Corporate Social Responsibility, “the speech you have at the party”.

But when Nilsen became Schibsted’s Group Compliance Officer, and now ultimately the Head of Sustainability, she got serious.

Her first step was to make sure the company’s Sustainability Report 2017 met the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) standards on measurement and transparency. Doing this meant Schibsted’s prospect as an investment improved, as the perception of their Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) risk went down.

“I went to the CEO… and that was when coming from finance was very handy because I speak their language. I know we have to earn money, but we have to do it in another way.

“And so I could tell them that ‘if we don’t have sustainability high up on our agenda, the investors will not be interested, potential recruits will not be interested, and you will lose the best people you have’.”

Seeing opportunities

“I could kind of go through and [show that] the risk of not thinking about this is huge. Look at how Facebook is having scandals with Cambridge. It’s not all companies that can take that kind of scandal.

“But my main point in those conversations was that, ‘yes, we have to comply with laws and regulations and all these things. But that goes without saying because that is kind of a ‘housecleaning’. What we need to do is look at opportunities’.

“We can actually earn money and at the same time be sustainable, take good care of the environment and society. But we just have to open our eyes.”

A year later, Kristin Skogen Lund, an experienced executive who had in the early 2000s led the Schibsted-owned Aftenposten, joined as the group’s first female CEO.

“When she presented the strategy for Schibsted, we have a pyramid, and on top we have ‘purpose’, ‘make sure it matters’. And I was so happy I could just cry because that is sustainability. It’s all about making sure that sustainability is in the core of our business. It is kind of the ‘higher sky’ you’re looking towards in everything you do.”

So in autumn 2019, Schibsted took a big look at what mattered.

What matters?

“We did a lot of benchmarking against our peers and others, and we looked at the risks and opportunities. And we did a lot of stakeholder dialogues. We asked a lot of questions, got a lot of answers, and we asked our users, readers, our advertisers, investors and the board. And we had like 3,500 answers to this.

“And then we kind of collected that into one result. And then I asked the executive team, ‘what do you think about this?’. I got 90 minutes with the executive team, which I was very pleased to get, and kind of landed on ‘OK, these are the aspects of sustainability that is important for Schibsted’.”

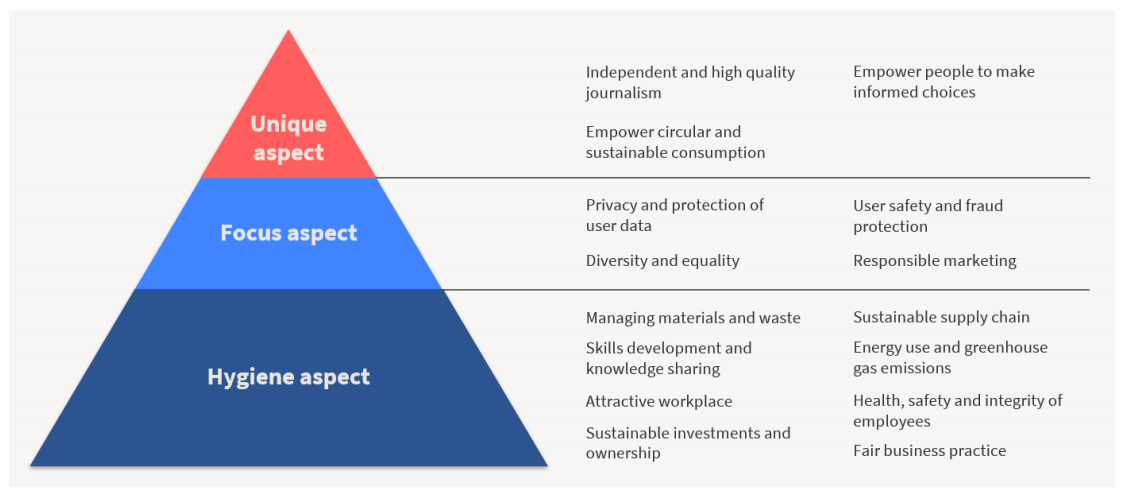

For the company’s Sustainability Report 2019 then, the group used both GRI and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) reporting standards to devise a hierarchy of sustainability issues that were collaboratively decided to be material to the business.

“And they are the responsibility of the executive team,” Nilsen explains. “So I have had meetings with every one of them and set long-term ambitions, short-term targets, action plans, KPIs to measure and so on.

“And they are the responsibility of the executive team,” Nilsen explains. “So I have had meetings with every one of them and set long-term ambitions, short-term targets, action plans, KPIs to measure and so on.

“So it’s not my goals. It’s not my ambitions for sustainability, it is out in the business areas and in the group functions.”

Tackling the supply chain

At the bottom, so-called ‘hygiene issues’ are things like supply-chain management.

“So now we have a supplier code of conduct, which is also reflecting our own Code of Conduct,” Nilsen says. “And it’s, of course, in alignment with human rights… and all those international standards.

“And the thinking is now that, whenever we sign a contract with a new supplier or we renew a contract, this will be part of the agreements. We are mapping the risk for those companies, where are the highest risks, and that could be country-related as well. And which companies should we go for first.

The company has software that identifies high-risk areas, flags them with suppliers so they know what needs to change, and they help them change their practices – or they stop using them.

One marketplace presenting a sustainability risk is its huge one in used cars. “It will at some point disappear,” she acknowledges. “So we’re seeing those business opportunities moving into rental, leasing, sharing, that kinds of business with cars, for example.

An area that has been challenging for the entire industry, due to its complexity, is measuring the environmental impact of digital networks, but Schibsted is currently testing a new tool that has just been created by the DIMPACT collaboration out of the University of Bristol in the UK.

“How are you calculating the electricity you are using from when we have made a product and until it’s read or streamed or heard or whatever the users are doing? Nobody has been able to do this because it’s too complicated, Nilsen adds.

A remaining problem for any news media organisation is the reliance of digital media technologies that appear to be inherently bad for the planet. We are lucky in the Nordics though, with our high share of renewable energy.

Responsible marketing

While still reliant on advertising, ‘responsible marketing’ also makes it onto the company’s sustainability pyramid as an ‘focus aspect’.

“We had Extinction Rebellion rallying outside our offices because we have a very popular podcast in one of our newspapers – and one of the largest oil companies in Norway had three podcasts with that newspaper brand.

“We may have advertising for Black Friday, but on the other side, we are trying to make people reduce their consumption and go into more circular consumption. We have advertising for gambling. And on the other side, we are writing about gamble addicts.

“So what we want to do is map all those dilemmas and see if we need a policy to regulate what kind of advertising can we actually do.”

She points to the UK Guardian’s decision to reject fossil fuel advertising in its bid for sustainability – but also acknowledges Norway’s almost synonymous link with fossil fuels.

“I want the people involved being able to say, ‘OK, yes, we do this because’, ‘we can have advertising for this because’. We have to decide, and this is not easy because we have different types of companies and so on, but we need to have a conscious relationship across the group to what we’re actually doing. And that is it in itself is something new.”

Measuring ‘brainprint’

But, perhaps most interesting, is the company’s consideration of its “brainprint”.

“On the top, you have what we call ‘unique aspects’. And this is really our business. This is our journalism. This is our marketplaces and this is our Next companies. And the thing with the pyramid is that the higher up in the pyramid you get, the higher is the positive impact on society and the environment.

“We are the kind of company that has much more ‘brainprint’ than we have footprint. We affect people’s minds. We are moving them and we are giving them the power to take better decisions.

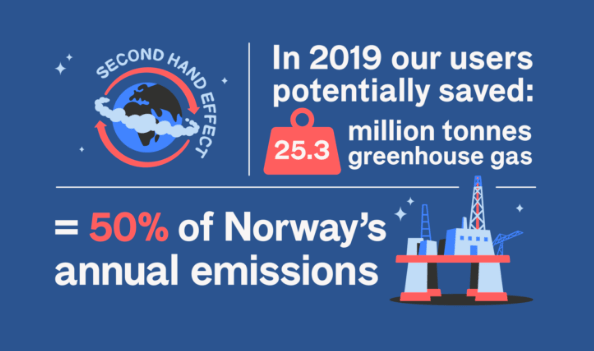

“What we do with our own emissions, is of course important, but we are really good at measuring environmental effects. Our own emissions are quite small compared to what we are able to accomplish by offering marketplaces for second-hand trade.

“We have done that calculation to see how much is that effect on society and for 2019, the calculation shows that for 12 of our marketplaces, we have potentially saved CO2e emission equal to 50 percent of the total emissions in Norway for one year. Huge figures.

“We are not good at measuring our effect on society. Like ‘how do you measure your journalism?’. ‘How do you measure the content impact?’. So that is a project we’re starting now.”

But, of course, here there are considerations about objectivity.

“It is a discussion. ‘Should we be just mirrors, or should we be movers to kind of nudge society towards something that we think is for the best?’ And it’s a difficult discussion because the newspapers are supposed to be objective.

“Of course, this is part of what we are doing, because, especially on our marketplaces, where we facilitate second-hand trade, we are nudging people a lot. ‘How can you take care of your things?’ We have written books about it… So we have ‘here are some tips on how you can take care of your things’.”

Making changemakers

Given that Nilsen has only just made her first team hire, this all sounds like a lot of work, so she’s created a Sustainability Changemaker Programme at Schibsted where 15 people from across the group, genders, business function and country, get to use 10 per cent of their time to work on sustainability.

“And then we’re looking into like ‘what are the business opportunities within the circular economy’, ‘what are new business opportunities within news media?’.”

She does not believe that financial and environmental sustainability are mutually exclusive, “but you need to grow in a different way and you need to measure differently”.

“It’s not enough to just look into the financial terms because then you are not pricing the externalities,” she agrees. “You have to put the prices of everything, of society and environment, into the calculation. And then you can start looking at, ‘OK, what are the terms of growth, then?’.”

Despite all of Schibsted’s success, she says it will take even them a lot of time to become mature in these areas.

The company’s diversity work so far, including using AI to understand whether using images that are more representative of readers can increase subscriptions (it can!), has been quite limited to gender.

Nilsen does put a large amount of this progress down to Kristin Skogen Lund’s leadership, but inspiring leaders aren’t quite enough.

Next, Nilsen says, “it’s about how can you give your leaders, your managers the right tool in order to unlock the potential that we have in a diverse workforce, to create innovation, to create value?”.

“Because this is all about mind shifting and you have to start thinking differently. You can’t look at it as a compliance, that you just ‘do no harm’ and give some money to charity and you’re off the hook. This is all about taking it into your core.

“I love the expression, I heard it the other day, that ‘diversity is having a seat at the table and inclusion is having a voice and belonging is being heard’, so if you can get into that type of culture and make sure that people are heard, then you will have the right thinking.”

CONTACT

Britt Nilsen, Head of Sustainability at Schibsted

Twitter: @NilsenBritt @SchibstedGroup