NRKbeta: public service media innovation for the 21st century

As media labs go, NRKbeta, from the Norwegian public service broadcaster, pitches itself less as a lab, more as an innovation service for 3,500 staff working on behalf of 5.3 million people spread across the country’s vast, mountainous geography.

Anders Hofseth has worked in this team for a decade and he’s still a part-time journalist for the nrkbeta.no blog, where NRK’s insight and innovation team started, but now he also acts as an internal, strategic advisor to the octogenarian organisation.

“The initial opportunity was given to us in around 2006. It started out as a blog because that was something people did in 2006. Several of us had private blogs writing about things we were thinking about and doing. The question was asked – ‘shouldn’t this be something that is part of our organisation?’.

“We experimented a lot with publishing in the early days. Slowly that’s matured into a technology and media vertical for NRK and now we’re specialising – some of our team are writing, some doing R&D, some advising the organisation. It made sense that it happened like that 15 years ago, but maybe wouldn’t play out the same today.

Asking tough questions

“Our remit is to ask uncomfortable questions, in a constructive way, of course. We understand the point of public service. We understand how the media works, how a lot of technology works and our role in society. We are able to say things that we need to say and know who to say it to.

“When people ask me what I do, the short answer is – I try to understand change on behalf of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation.”

Hofseth, who was the inaugural Google Digital News Fellow at the Reuters Institute at Oxford University back in 2016, eschews the ‘media lab’ label.

“We used to call ourselves the ‘sandbox’ of NRK. Doing things that maybe shouldn’t be done by the wider organisation before being tested first.

“We were never built. We were just given permission to do things a long time ago. And the organisation sees it makes sense to let us do our thing. But we do have a small physical space and a publishing platform.”

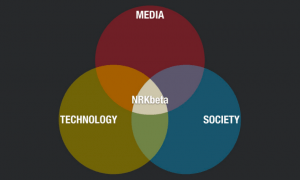

He also emphasises that their team of seven works at the intersection of technology, media and society, the latter deeply informed by the public service remit of the wider organisation.

“The reason we’re here is for the audience – a big measurement for us is – ‘what does the audience want?’, not ‘what do we want?’.

“It’s a Venn diagram – technology has no value in itself, neither does media – where they meet society is where they change things and where we work.

Where NRKbeta works

“NRK in general is in a very good position as media companies go – it reaches 89 per cent of the population daily – including people in their teens and 20s, and we are broadly trusted by a lot of the population.

“The main bonus of this is – something our head of commissions said a few weeks back – we don’t need to panic about losing our audience, we have the opportunity to think ‘we have their attention, how should we use it?’.

“10 years ago there was a big status difference between being in TV and online news, but that has flipped 180 degrees. We have challenges with the transformation from linear to online content, but not on a level with many other public service broadcasters.

Decoupling funding from platforms

“What we did in NRK several years ago was to stop saying money was tied to specific platforms – now you’ve got one budget for what you need to do, and you can do the thing that’s best on whatever platform.

“From top management all the way down, we have people who understand the changes that need to be made and we are advising on things where we might have something to say.”

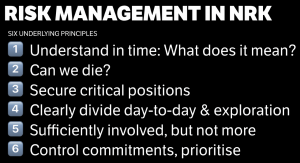

In terms of how they ‘do innovation’, the team is not wedded to sprints or hacks, but is the first port of call for understanding “shiny new things” via its risk management programme.

“We started this a few years back, centrally analysing changes in technology, society and media, and contextualising early what could they mean for our mission as a public service broadcaster. ‘What will we need to know to handle it?’. ‘Is it something we can die from?’. So we don’t have to handle things after they’re a problem.

“We have a small group where we meet frequently to discuss these insights – and we understand not just how publishing, text or filming works, but we have a larger outlook on how it will touch us at different levels of the organisation, and we have the right people to ask.

How NRK does innovation strategy

“From time to time, new things happen and you have a general panic about trying to ‘be first’. We take care of understanding those changes – such as how to handle smart speakers or virtual reality – and we try to understand and contextualise those things early.

“When the first smart speakers were launched in Norway in 2018, we had already said ‘how can this affect us?’. ‘What will need to change for us to use this in a good way?’. If they had changed the market, we’d have already known it would hurt ‘here’, ‘here’ and ‘here’.

“With things like Virtual Reality or 360° video, people were talking about how they were going to save publishing. But we said ‘no we’re not doing that anymore, we’re handling those things in small projects that are cross-functional and will be killed after we understand and we’ll know enough to move on’.

From insights to R&D

We could assure our organisation that VR would not change us as media in the foreseeable future. As an organisation, this helps us focus on doing what we have to do, rather than bleeding to death on a lot of useless things.

“One example of something we’ve been talking about over the past two years is TikTok. It’s illustrative of changes of how parts of the audience are consuming content and how users generate the content themselves, even though that’s really a previous decade idea.

“We ask ourselves, ‘what parts of technological innovation do you leave to large companies instead of doing it yourselves?’. The iPhone was launched 13 years ago and the media innovated a lot for smartphones in the early years. Today a lot of exploitation of more advanced features have been left to Silicon Valley and China. Having sufficient control of things like this helps us know what will really matter.”

Alongside insights for risk management, some of the NRKbeta team is charged with making innovation happen internally.

“We have a few people doing more hardcore R&D on technology for broadcast and digital. One of our biggest successes here was a simple automatic rig built by one of my colleagues that has made it possible to cover all the microphones in a radio studio with one camera each, and so automatically make a TV programme without anyone manning cameras or editing.

“Before, this would take a lot of people, so it helped us move resources to where they would make more difference. It also showed that we didn’t always need to buy big, expensive proprietary systems for making TV. Now the NRK has started building things ourselves for a fraction of the cost. So it’s changed how we worked, in moving resources, and helped us produce a lot of good TV content from things that were previously audio only.

“Another thing, which got us international attention, was the ‘Quiz to Comment’ project where we were testing people’s understanding of a story they’d read before they could comment. What it did at the time when it was released was address some deep underlying issues in many societies around disinformation in online debate.”

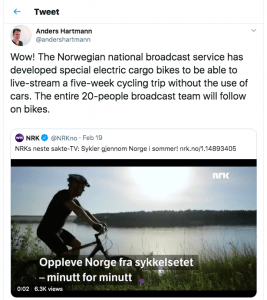

NRK is also credited with pioneering so-called ‘slow TV’ or ‘marathon’ broadcasting projects – which this year will see them covering a five-week cycling trip with the full kit carried on bikes.

The NRKbeta team does look outside the organisation for insights, but only so far as it needs to.

“More and more, we’re developing into something that’s leveraging energy from other parts of the organisation, so we don’t do everything ourselves. People come to us and say ‘I’m struggling with doing this or that’. And we say ‘maybe you should talk to that person over there?’. We’re not doing innovation in a small, closed group.

“We do speak to our networks – at the BBC and others – and we regularly observe the cutting-edge of what people are discussing in the business. We’re probably spending a lot less than many others on insight and research. One of the few things we spend money doing is going to a few conferences a year to contextualise what the media business is discussing.

“NRK did get a new remit a few years back and one of the things we were told to do was have a responsibility for media diversity in Norway. And it’s ended up with us being more open to cooperation, particularly sharing all the insights from NRKbeta. We have a ‘recent insights’ talk, which is around an hour long, and last half-year we presented it around 30 times – half within NRK and half to others outside. We tell other Norwegian media everything we tell senior management at NRK.

“You could think this has to be super secret because people will steal it – but you have to have an organisation that will act on these insights – so as long as we have this organisation, we shouldn’t be worried. You’re more competing against other kinds of business than media.

Gladly, his team’s work isn’t measured in a conventional sense, Hofseth explains.

“We’re not measured by hard measures – we’re measured by what the organisation perceives that we can help them achieve. So, as long as most people in the organisation see us as a force for good, I think we’re good. The important thing is that we’re able to deliver, to answer most questions anyone – from the Director General to a stray journalist somewhere – might ask us.

The next 50 years of public service

“A good way to work with insight and innovation is to spend enough time analysing the insight before acting on it. An important reason we’re able to do things is that we separate the thinking and the analysing, from the power structures and budgets, so we’re able to think quite coldly about what things mean. We discuss not from the perspective of self-preservation, but ‘what would it mean for our business in 50 years?’ and ‘how do we get where we want to be?’.

“We have been doing a lot of things for reasons we understand, so after having tried something that seemed a bit risky the first time, then repeating and doing that, and changing and moving forwards, we’ve been able to shift our balance.

And what’s next for innovation at NRK, and for Hofseth’s work?

“I’m going to do the same thing I did last year. The insight work is a one-year cycle where we start to amass all the changes that have happened since last year. Then we chew on that. Then we’ll make our presentations for people across NRK.

“I’ve been doing this for 10 years – and there have only been two really big changes in that time. One is the mobile phone and particularly when the iPhone arrived in 2007 – if you go onto Wayback Machine and see 10-year-old web pages – that changed a lot. And the other is platforms and social media and those things being VC-backed, meaning they came into this with a completely different set of ethics to what we have.

“Public service is an idea that you used to be able to get governments to build an organisation around 50 or 100 years ago, but you couldn’t do that today. It’s something we need to take care of. The long-term survival of public service media depends on broad public trust, love, and daily relevance.

“Our purpose in this is helping the NRK adapt and stay relevant to the audience, and their needs and usage patterns through a period of massive change. So everything we do we consider within the perspective of helping secure and facilitate the public service mission of the NRK: To inform, educate, and entertain Norway.”

CONTACT

Anders Hofseth, Photo Kim Erlandsen, NRK 2020

Anders Hofseth, journalist and strategic advisor

Twitter: @andorand